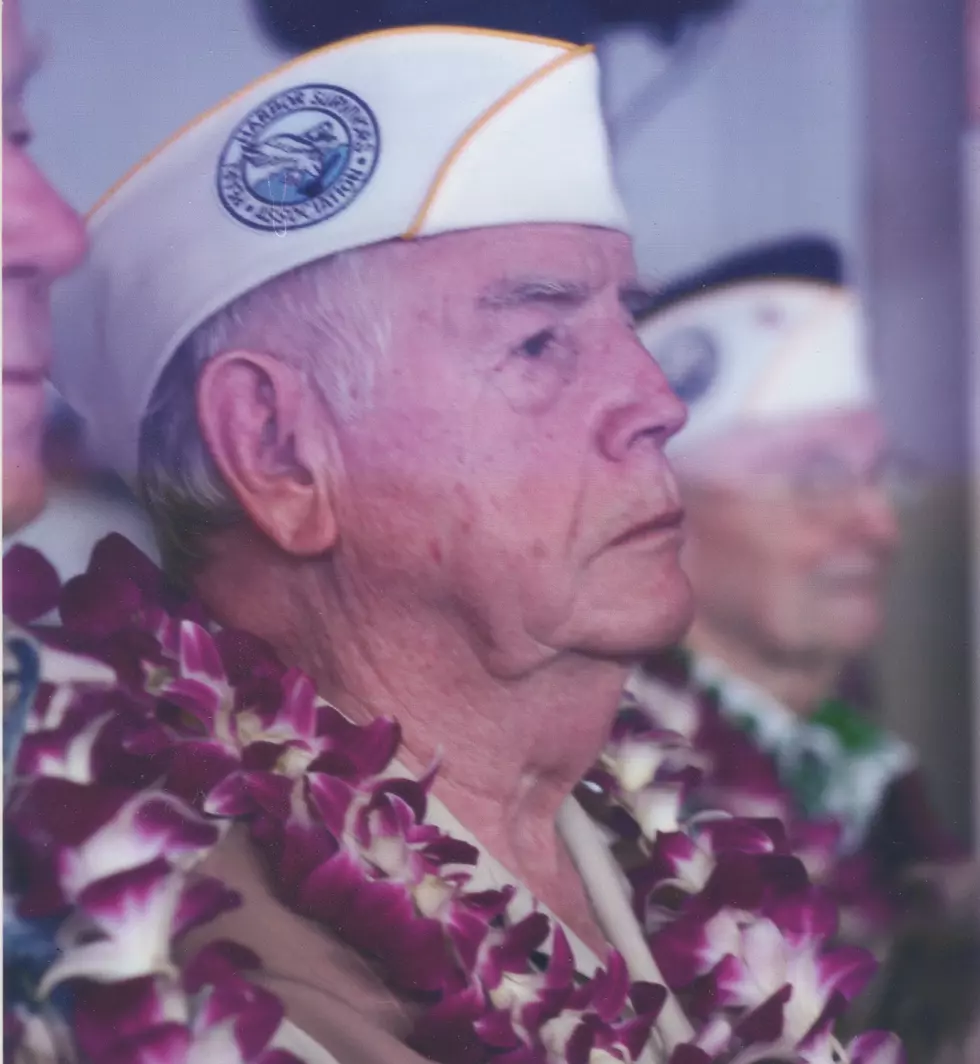

Goodbye Again to a Dad and a Pearl Harbor Survivor

I wrote most of this two years ago, and now have added a few memories and the unanswered questions of a child who wonders about parents who frustratingly said so little.

Like the rest of us, you didn't ask to be born in a certain place at a certain time with certain circumstances.

You didn't ask for the U.S. involvement in World War II to start 81 years ago a few miles away from Waikiki where you were swimming that morning.

I'm pretty sure you didn't volunteer to pick up severed heads, assorted limbs and globs of unidentifiable flesh at the airfields after the attack.

But you survived, had an awesome life and embraced eternity with open arms like few people I've known.

======================

Dad,

Saying goodbye — “God be with ye” — happens a lot: friends who know they’ll see each other next week; parents who will see their college students at the end of the semester; families who hope to see their children in the military after a deployment; after an angry but temporary epithet after a quarrel with a friend; and bereaved relatives to their deceased loved ones with the hope for a reunion in the world to come.

This goodbye refers to the latter, specifically in the context of what happened 81 years ago today when you, my dad, Sgt. George T. Morton, and an Army buddy skipped church to hang out at Waikiki Beach.

You dropped out of school probably at age 14 or 15 -- the decision of eating or education during the Great Depression was pretty simple. You were surviving as a street kid in the Over-the-Rhine -- a "bring your own switchblade" neighborhood -- of Cincinnati and enlisted in the U.S. Army at Fort Thomas, Kentucky, on Feb. 8, 1940. You had a choice of being stationed in Panama (nah, same hemisphere), the Philippines (too far away) or Hawaii. After transferring through the Army bureaucracy from Kentucky to Brooklyn, New York, and by ship down the east coast through the Panama Canal, you made it to Oahu.

You knew there was the possibility of war with Japan, but Army life went on.

On Dec. 7, 1941, you and your buddy hauled a 30-pound portable radio for the music to harmonize with the surf and probably a few giggling girls getting a glimpse of a 20-year-old man who should have been a model.

A little before 8 a.m., the music cut out, returned, cut out with some confused chatter and finally an order for all military personnel to return to their bases. You caught a ride on a bus. The driver would stop every few blocks to look up for planes, and eventually took you to your base at Fort Armstrong on the waterfront of Honolulu Harbor where you offloaded light tanks and ordnance from ships.

After the initial musters, you were initially ordered to dig slit trenches in the coral, which was virtually impossible. So you filled and distributed sandbags instead. The fear of an invasion was real. The sound of waves lapping on the beaches enhanced the paranoia.

Despite their basic training, skittish soldiers would fire their weapons at the dark, followed by other soldiers firing cuss words at each other in the dark because other soldiers were firing their weapons in the dark.

Fort Armstrong wasn’t a direct target being about five miles from the harbor, but you told me it got hit by an anti-aircraft shell or bomb that tore up some vehicles. Old maps and photos showed a base with barracks. warehouses, ancillary buildings and parade grounds. You and your fellow soldiers spent the nights on the parade grounds, because that posed less risk from a bomb than being in a building.

For the rest of the war, you continued your quartermaster work, and experimented with ordnance that would work best on the frozen western Aleutian Islands, the only U.S. territory captured by the Japanese.

Later, you were transferred to Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland to test ordnance with some early computers.

Post-war, you earned an engineering degree at The Ohio State University; married; moved to north of Cincinnati to build our house -- now under the Ronald Reagan Cross County Highway; have three kids; earned a couple of master's degrees, built jet engines for General Electric; lived in France for three years to build jet engines there; retired to pursue other interests including being a docent at the Taft Museum in downtown Cincinnati -- a literal stone's throw from the elementary school you attended.

Sometimes, maybe a lot of times, it wasn't easy for this fugly, extremely nearsighted, socially inept eldest son to deal with a dad whose parents -- who "got around" as you put it -- split when he was probably 8 and had to deal with whatever emotional issues that caused..

Your anger frightened me and often sent me into my dopey introverted fantasy landscape that remains a friend.

My embrace of right-wing politics and later evangelical Christianity gave me purpose but wrecked my personhood and relationships, and for that I'm still most sorry because it got in the way of communicating with you.

Through my childhood and beyond, you didn't talk much about your presence at what a lot of historians regard as one of the most pivotal moments in the 20th century

You shirked questions about whether you would go back to Hawaii. Not just for the war memories but, hey, you were 20 years old and surely you had some interactions with Hawaiian babes. And for crying out loud, it wasn't like asking a Desert Storm vet to revisit Kuwait to see a thousand square miles of sand.

Something changed in the late 1980s, though. From what you told me and from what I inferred, you returned to Honolulu and visited the Arizona Memorial. And nearly 50 years of emotional garbage blew up. The Pearl Harbor Survivors Association had people around to help with the likes of you who had repressed so much.

In 1991, a long year of unemployment for me, we were having lunch on a floating restaurant across the Ohio River from Cincinnati.

The next day, you would fly to Honolulu for the 50th commemoration.

So, I, edging into reporter mode, asked what you did on Dec. 8 and after.

You told me you were sent to to the nearby airfields to pick up bodies and body parts. You took them to the city morgue, dusted them with formaldehyde and stuffed them in pillow cases or bags used for cots. "Death has a smell that clings to you.” While he got used to the smell, others didn't. People in dining halls lost their appetites real fast when he walked in, so he showered before meals.

You also had the presence of mind to buy Honolulu newspapers from Dec. 8th and Dec. 9th. (See gallery.)

In 1996 I interviewed you for the Casper Star-Tribune and learned you'd met Casper resident Walt Becker, founder of Becker Fire Equipment Co., and perhaps the only sailor in World War II who had three ships shot out from under him starting with the Oklahoma.

We went together for the 60th commemoration -- three months after 9/11/2001 -- and the 65th in 2006. The latter was extra-special for me because U2 played their last concert in their Vertigo tour at Aloha Stadium on Dec. 9. Pearl Jam opened the show.

Health and other issues derailed plans for future visits.

Four years ago, we family gathered for a Pearl Harbor ceremony in a little park in northeastern Ohio.

We saw each other on 22, 2019, for your 98th birthday. I took a selfie of us. You asked what I was going to do with it and I responded that I would post it on Facebook so my friends could see it.

A bunch of us thought you would live well beyond 100.

That was not to be.

On Aug. 26, the staff at the assisted living facility dressed you for breakfast. Within a few minutes you were gone.

A long time ago, I vowed to revisit Honolulu after your death for the next Pearl Harbor commemoration.

I did in December 2019, surrounded by the beauty of Hawaii and the subtext of the horrors of 78 years before.

In 2019, the number of survivors had dwindled sharply to maybe two dozen from the thousands we saw in 2001 and 2006.

However, there will always be remembrances

At your funeral, I read from Isaiah 40 and my favorite punk poet and singer Patti Smith. You probably wouldn't have been fond of her, but she nailed it.

Rise up hold the reins

We'll meet again I don't know when

Hold tight bye bye

Paths that cross

Will cross again

Paths that cross

Will cross again.

Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Monday, Dec. 8, 1941

More From K2 Radio