Block Of OTC Morning-After Pill Sparks Debate

WASHINGTON (AP) — It's the morning after and the controversy over how to sell emergency contraception still looms.

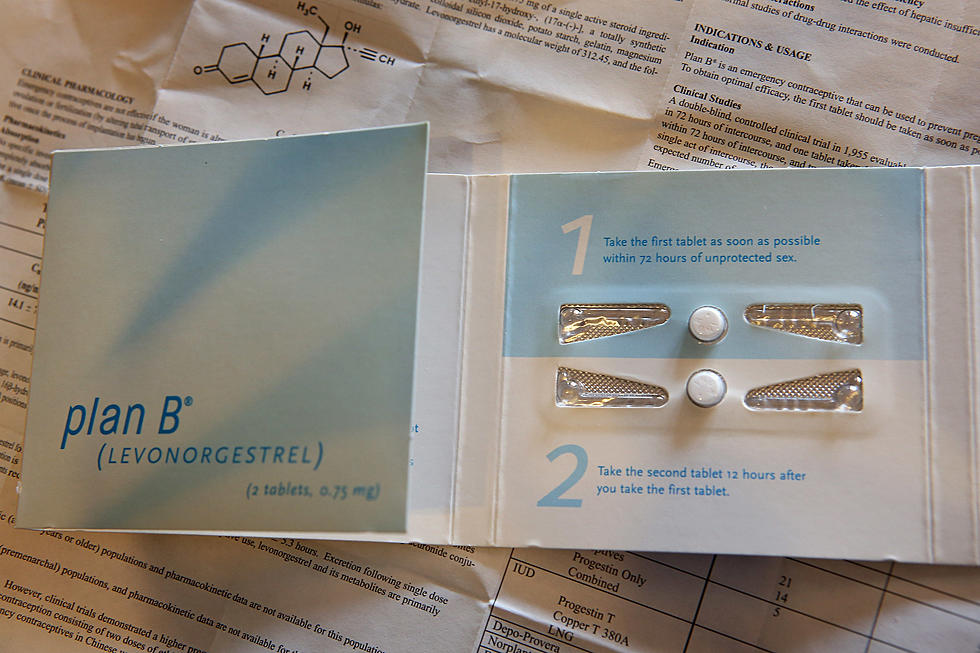

The Obama administration's top health official stopped plans Wednesday to let the Plan B morning-after pill move onto drugstore shelves next to the condoms.

Overruling scientists at the Food and Drug Administration, Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius decided that young girls shouldn't be able to buy the pill on their own, saying she was worried about confusing 11-year-olds.

For now, Plan B will stay behind pharmacy counters, available without a prescription only to those 17 and older who can prove their age.

It was the latest twist in a nearly decade-long push for easier access to pills that can prevent pregnancy after unprotected sex, and one with election-year implications. The move shocked women's health advocates, a key part of President Barack Obama's Democratic base, as well as major doctors groups that argue over-the-counter sales could lower the nation's high number of unplanned pregnancies.

"Secretary Sebelius took this action after careful review," Obama spokesman Nick Papas said. "As the secretary has stated, Plan B will remain available to all women who need it, and the president supports the secretary's decision."

Sebelius' decision is "medically inexplicable," said Dr. Robert Block of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

"I don't think 11-year-olds go into Rite Aid and buy anything," much less a single pill that costs about $50, added fellow AAP member Dr. Cora Breuner, a professor of pediatric and adolescent medicine at the University of Washington.

Instead, putting the morning-after pill next to the condoms and spermicides would increase access for those of more sexually active ages "who have made a serious error in having unprotected sex and should be able to respond to that kind of lack of judgment in a way that is timely as opposed to having to suffer permanent consequences," she said.

The move will anger many Democrats. Sen. Patty Murray of Washington, a member of the Senate leadership, already was asking Sebelius to explain her decision. But it also could serve to illustrate to independents, whose support will be critical in next fall's presidential election, that Obama is not the liberal ideologue Republicans claim.

Nor will this end the emergency contraception saga. In 2009, a federal judge said the FDA had let politics, not science, drive its initial behind-the-counter age restrictions and said it should reconsider. At a hearing scheduled in federal court in New York next Tuesday, the Center for Reproductive Rights will argue the FDA should be held in contempt.

Sebelius' decision pleased conservative critics.

"Take the politics out of it and it's a decision that reflect the concerns that many parents in America have," said Wendy Wright, an evangelical activist who helped lead the opposition to Plan B.

"This is the right decision based on a lack of scientific evidence that it's safe to allow minors access to this drug, much less over-the-counter," said Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa.

FDA Commissioner Dr. Margaret Hamburg made clear that the decision is highly unusual. She said her agency's drug-safety experts had carefully considered the question of young girls and she had agreed that Plan B's age limit should be lifted.

"There is adequate and reasonable, well-supported and science-based evidence that Plan B One-Step is safe and effective and should be approved for nonprescription use for all females of child-bearing potential," Hamburg wrote.

Pediatrician Breuner said taking Plan B, which contains a higher dose of the female progestin hormone that is in regular birth control pills, wouldn't harm even young adolescents.

Sebelius didn't raise safety concerns. She said maker Teva Pharmaceuticals hadn't proved that the very youngest girls who might try Plan B would understand how to use it properly.

A Teva-funded study tracked 11- to 17-year-olds who came to clinics seeking emergency contraception. Nearly 90 percent of them used Plan B safely and correctly without professional guidance, said Teva Vice President Amy Niemann. But Teva wouldn't say how many of the youngest girls were part of the study.

The company was determining its next steps.

Taking Plan B within 72 hours of rape, condom failure or just forgetting regular contraception can cut the chances of pregnancy by up to 89 percent. But it works best within the first 24 hours. There are two other emergency contraception pills: a two-pill generic version named Next Choice that also is sold behind the counter, and a prescription-only pill named ella.

If a woman already is pregnant, the morning-after pill has no effect. It prevents ovulation or fertilization of an egg. According to the medical definition, pregnancy doesn't begin until a fertilized egg implants itself into the wall of the uterus. Still, some critics say Plan B is the equivalent of an abortion pill because it may also be able to prevent a fertilized egg from attaching to the uterus.

More From K2 Radio